To understand the public view, we recently ran a series of focus groups across the country, including sessions in London, Glasgow, Bristol, Birmingham and Manchester. Participants were taken from a cross-section of society, reflecting the local demographics in terms of gender, age, occupation and ethnicity.

The message was forceful: the incessant demystification of the professions over recent years has taken its toll. The banking crisis, the investigation into abnormal death rates at Mid Staffordshire Hospital, the arrest and prosecution of newspaper editors and journalists, and the scandal over MP expenses which led in extremis to custodial sentences, have not gone unnoticed.

One focus group participant, the owner of a small London-based design business, expressed it thus: “Elitism doesn’t mean anything. It certainly doesn’t mean they are more attentive. Too many of the so-called professions operate like a closed shop. Self-preservation trumps all.” Another commented dismissively: “You can buy your way into anything.”

And a third, a working mother in Bristol, was sceptical about the nature and content of suggestions she received from professional advisers, irrespective of their qualifications: “They are not so creative, they are too tied into a set way of doing things. They plan well, but always inside a box. They find it impossible to deviate from the rules, and can’t deal with unusual situations.”

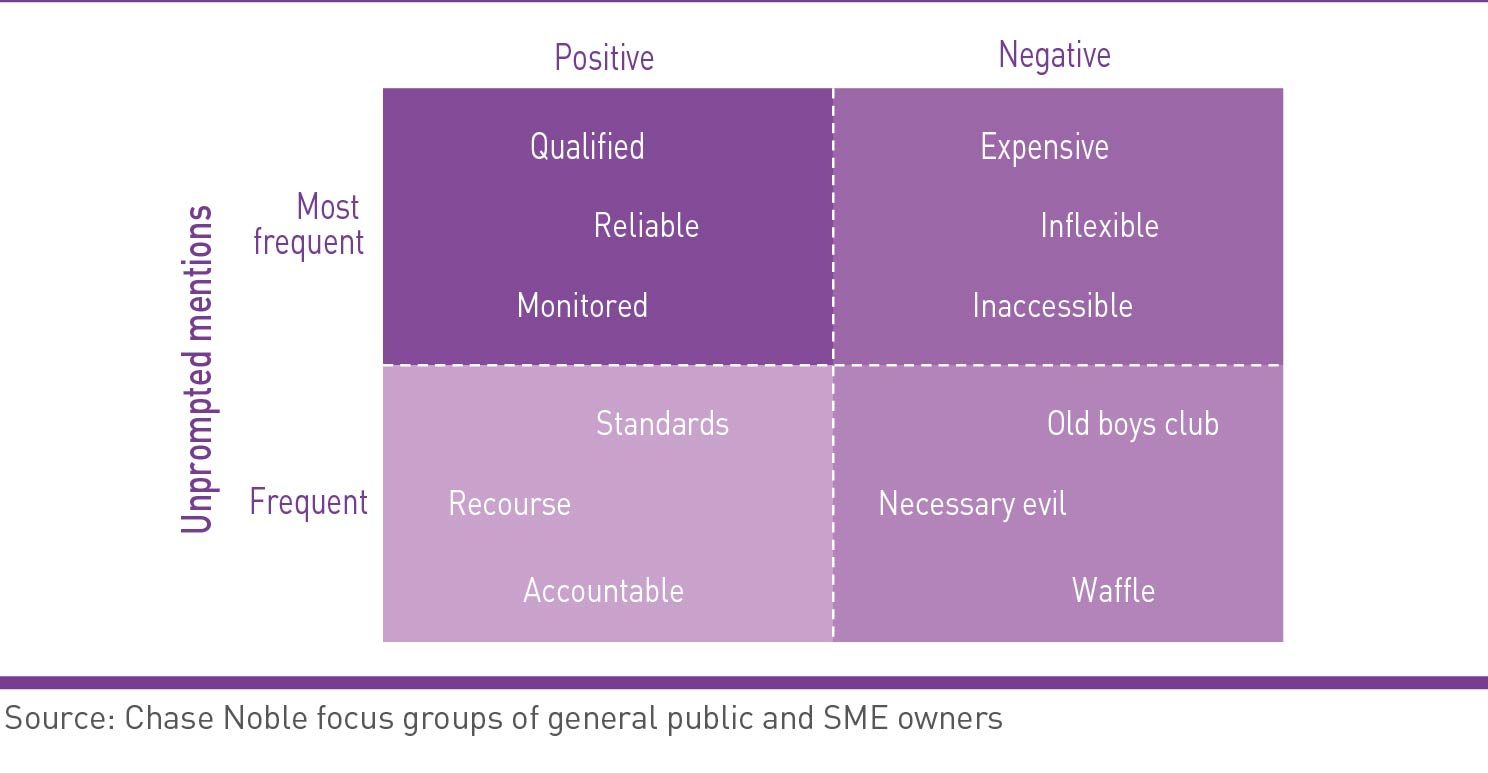

The words and phrases most frequently employed by respondents, including the most damning, are reproduced below.

FIGURE 1: Unprompted associations with the concept of professionalism

A further theme from the focus groups was that the commoditisation of information has profoundly affected the public mood. At a click or two, websites can be accessed on every conceivable topic, from the technical to the obscure, to the technically obscure. Knowledge is no longer a scare resource, hidden from wider view. Professionals have not acquired insights via some sublime alchemy that are impenetrable and beyond challenge.

“Facts are no longer the prerogative of the blessed few”

On the contrary, sites from Wikipedia to Yahoo Answers now provide a synthesis of material that, two decades past, was not available beyond the confines of elite institutions. The facts sometimes get distorted, misconstrued or wrongly-defined, but they are no longer exclusively the prerogative of the blessed few. Amidst this maelstrom of evolving knowledge, educational practices are struggling to remain relevant. Is entry into a profession determined by the ability to recite a canon of knowledge? Clearly, this has a role, but is it sufficient?

One focus group, comprised of aspiring professionals from diverse sectors, concluded that years spent in rote memorisation of key data was now redundant. Facts can be checked within moments; moreover, information can change so quickly – amended through legislation, different guidance, an updated evidence base – that relying purely on recollection veers towards negligence. On the other hand, there’s no short cut to competence in listening, analysing, interpreting and especially applying knowledge. The dictum of philosopher, John Dewey, that “we can have facts without thinking, but we cannot have thinking without facts” may need to be recalibrated for the modern era.

The Manchester focus group involved business leaders rather than young professionals or the users of professional services. Eight managing directors agreed the uncertain economic outlook was forcing them to be more frugal and less cavalier in funding the professional development of staff on an open-ended basis. They ask whether they can justify intense investment in upskilling their workforce when the next round of redundancies is just around the corner. They struggle to justify training budgets whose payback, if any, comes over the long term, when the boardroom preoccupation may be survival to the year end.

As the corporate meat cleaver hacks away at spend of dubious value, they see the payment of professional body subscriptions on behalf of employees as a relatively easy and pain-free target for cutting. This poses a challenge; one which professionals across the board are needing to meet with diligence, imagination and a dash of chutzpah.

“The concept of Chartered still carries caché”

But, amidst the scepticism, signs of hope for professionals and professional bodies could still be discerned. Participants felt the harshest generalisations were unwarranted and too indiscriminate. They recognise that tiers exist, and those who excel are a class apart. In particular, the concept of Chartered still carries caché. Respondents felt it symbolised a commitment to go beyond basic, satisfier standards. “It says to me they’ve put in a lot of effort,” said a young restaurateur. “There’s been a more rigorous seal of approval, ultimately it comes from the Crown,” added a project manager. When the soubriquet Chartered appears on business cards or office doors, the public seem to take a degree of reassurance.

The focus group delved at some length into the origins of this comfort and fortitude, and uncovered two assumptions. People assumed that a Chartered service would be more costly, but that it would likely offer better value: “The cost of a Chartered surveyor will probably be double your bog standard surveyor,” said an advertising agency receptionist. “But, it’s the top slice of the pyramid. If a Chartered surveyor advised me on installing a steel beam, I’ll be a lot more confident the house won’t collapse,” she added.

Respondents also asserted that, should something go awry, with Chartered professionals the process of redress and restitution will be smoother and speedier. “Chartered financial planners don’t need to wear pinstripes; flip-flops and shorts are fine,” said a Birmingham headmaster. “Because if they’re Chartered, and I lose out, they will deal with me fairly and the professional indemnity will pay up” .

In modern Britain, elitism is often stigmatised by desperate politicians in search of easy applause on talk shows and panels. But many other cultures maintain the uncluttered conviction that educational excellence is both a virtue in itself and of wider social benefit. It’s little wonder those countries where elitism is not only free from pejorative class overtones, but is embraced and celebrated, face the coming decades with optimism and confidence. They have seized the principles of achieving Chartered status, and encouraged its evolution from a quirky oddity of the constitution in a small island off Europe’s north west coastline into an archetype with global resonance.

“Members’ careers are more likely to include secondments to hot spots thousands of miles from London’s coffee shop”

International yearning for a Chartered title is one of the many factors that have led professional bodies to redefine themselves on a stage that stretches beyond narrow national borders. Members’ careers are more likely to include secondments to hot spots thousands of miles from London’s coffee shops. Corporations may see the UK as a shrinking, scarcely visible footnote to their global operations. And overseas governments and regulators, when introducing a new institutional framework or licence to practice, often approach UK practitioners for counsel. However, this isn’t quite the endorsement of British competence it might, at first blush, appear; since industrialisation had its origins in Derbyshire mills, overseas policymakers are often seeking to understand the errors and mis-steps that have littered Britain’s story for the past 200 years, in order to avoid repeating the same mistakes.

In the face of the age of cynicism, professional bodies need to maintain confidence in the concept of professionalism and the status of the Chartered motif. If the professionals’ pedestals are no longer as ubiquitous as soapboxes at Speaker’s Corner, hopefully they’re not yet extinct, or confined to museums alongside other historic curiosities.

“Often mimicked, never matched”

Custodians of the Chartered brand must resist short-term temptations or pressures to dilute. The label must embody in one simple descriptor the concepts of maintaining competence, looking ahead, applying knowledge, and fulfilling a public interest purpose. Following these precepts, the Chartered message may obtain a place without peer – as Rachmaninoff’s third, or the Mona Lisa, or Ulysses, or the Hanging Gardens of Babylon. Akin to the totalmente a mano label on a box of handmade Cuban cigars; often mimicked, never matched.